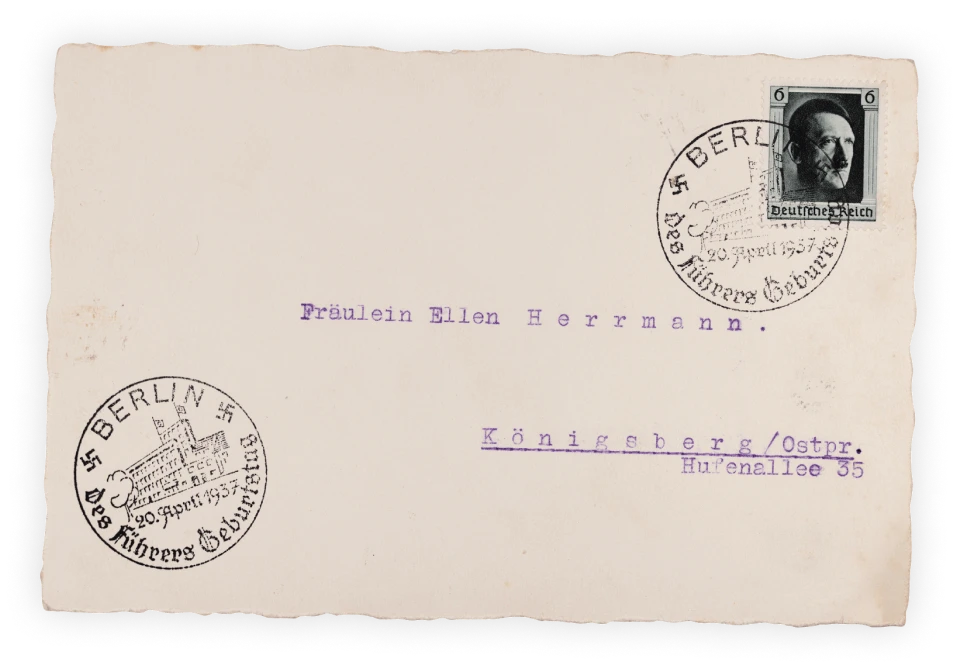

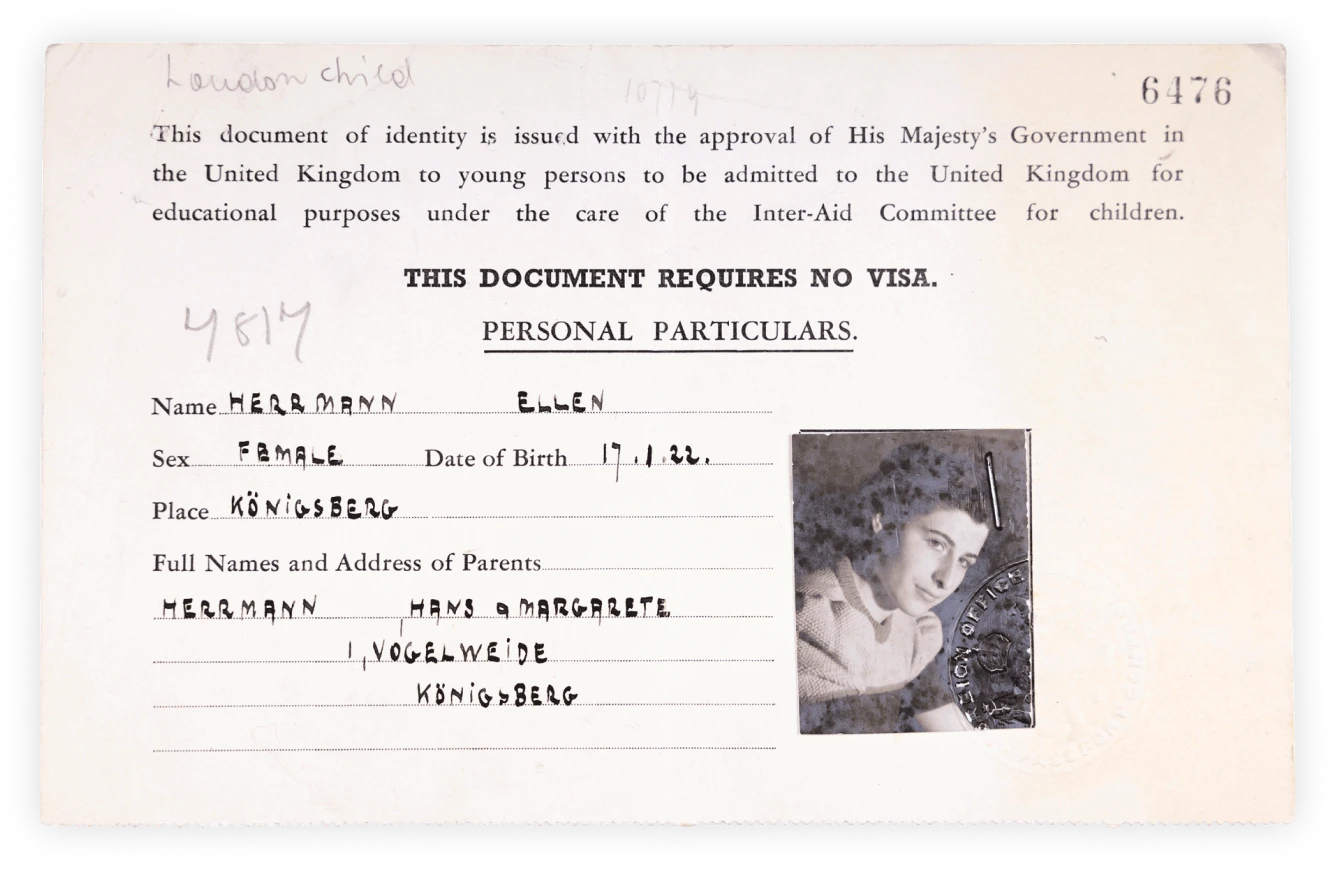

Ellen Rawson (née Herrmann) was born on 17 January 1922 in Kӧnigsberg in East Prussia, then a part of Germany.

1922

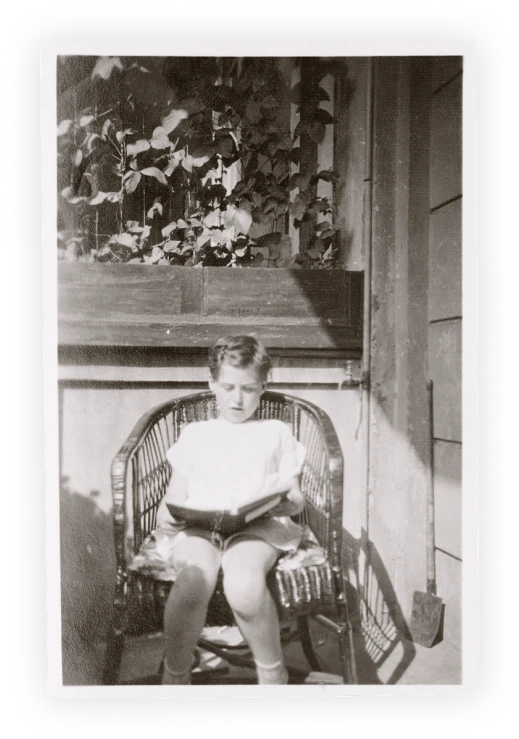

Ellen’s brother, Gert, was born on 31 December 1922.Seven years later, their brother, Heinz, was born.

As children, Ellen, Gert and Heinz played lots of games and their mother used to make time in the afternoons for them to play records. Ellen also loved and collected books. Ellen’s parents were great bridge players and Ellen herself started playing at the age of eight.

1935

When Hitler came to power, Ellen’s life didn’t change very much to begin with. But as the years went on, things got much more difficult and Ellen had to leave school when she was 15.

1938

In 1938, Ellen travelled to Mannheim, Germany, to train as a dressmaker. During the November Pogrom, she witnessed an antisemitic mob going down the road, smashing up Jewish homes and businesses.

It was after these terrible events that people began to think seriously about getting children out of the country. Ellen’s mother wrote to lots of people abroad and the only positive reply she got was from the Ladies’ Committee of the synagogue in Seymour Place, London, who guaranteed places for some children to go to England.

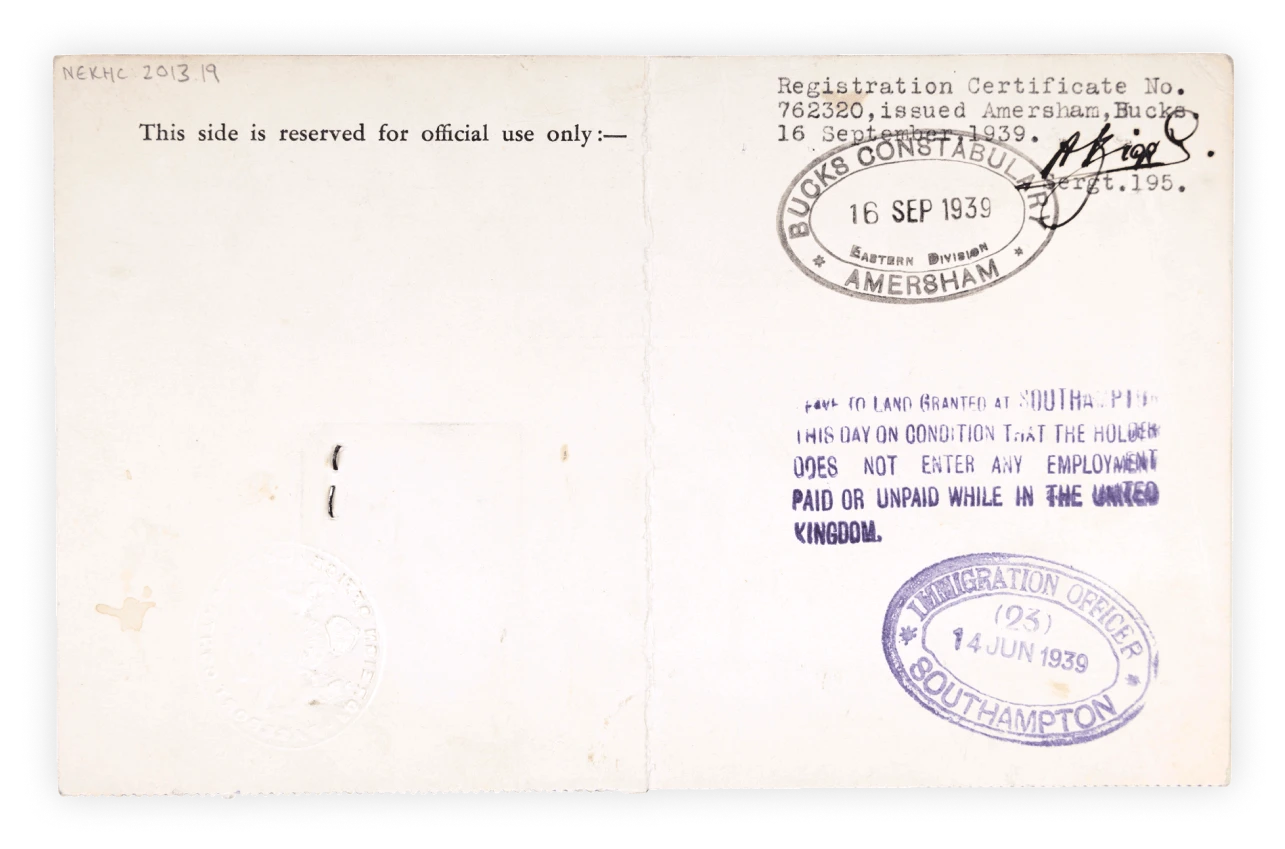

Ellen’s mother told her she would be leaving via the Kindertransport. Margarethe packed her clothes and a few small items she thought that Ellen might be able to sell in England, because children were only allowed to take a small amount of money.

Ellen eventually arrived in London. After a week in Islington Hospital due to a suspected case of scarlet fever, Ellen was collected by a lady from the Committee. She had lost her domestic help at home, so Ellen was told to cook, clean and do everything in the house. She would regularly sit on the stairs and cry.

Ellen was allowed to eat with the family in the dining room, but she couldn’t be paid as she didn’t have a work permit, so only received pocket money. It was an unhappy time for many reasons, and the most difficult part was that Ellen couldn’t speak English and it took her some time to pick it up.

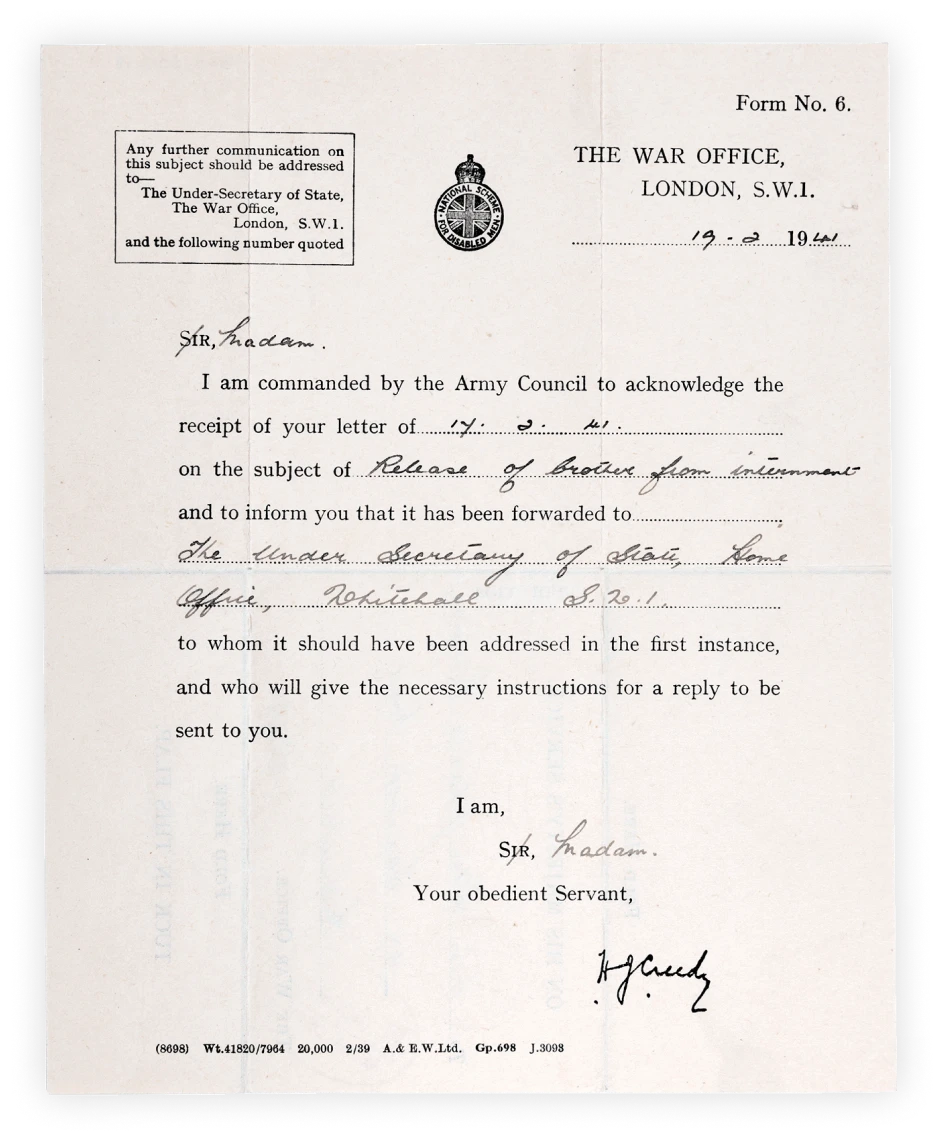

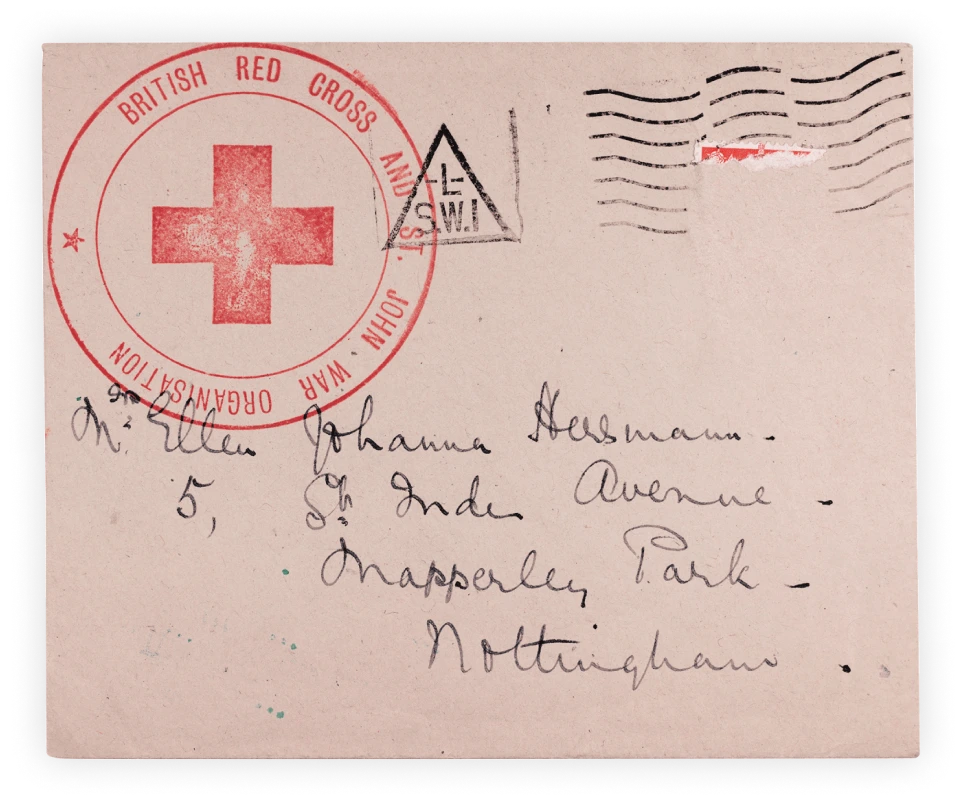

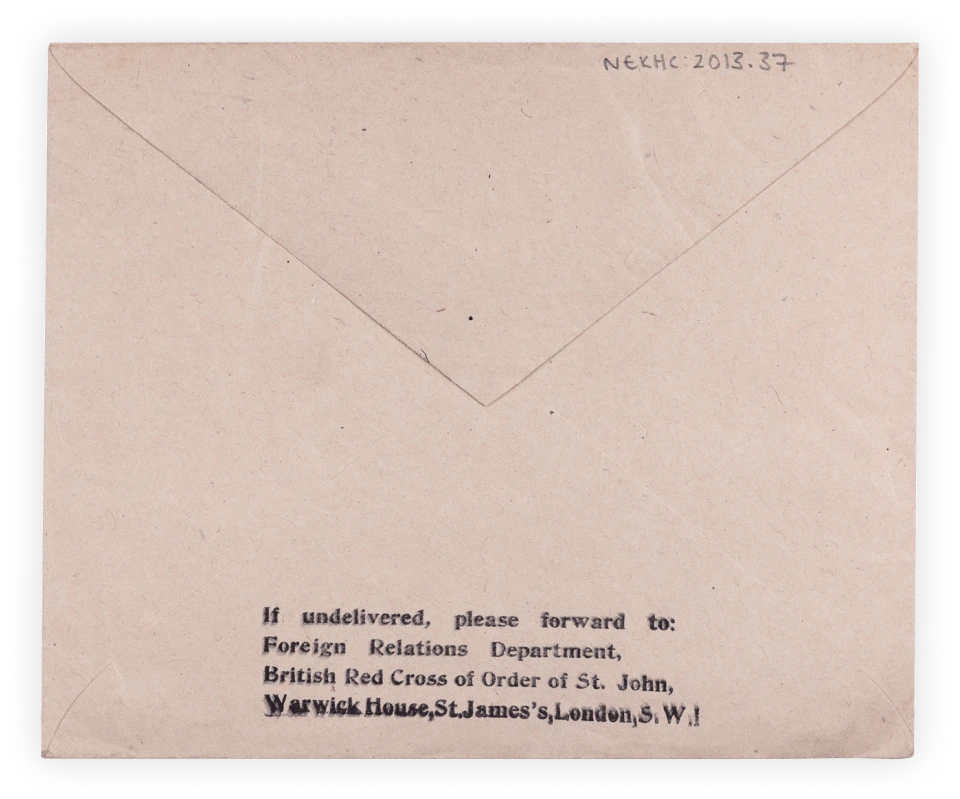

Ellen’s brother Gert also found refuge in England, entering with an agricultural working permit, but her youngest brother and parents were not able to escape. Communication between them and Ellen was restricted to sporadic Red Cross letters.

She was sent from one family to another (around eight in total) working like this, usually for just a fortnight. Sometimes she was happy with the family, sometimes not. Eventually, she found a job as a machinist in a Jewish firm.

Later Ellen married and moved to Nottingham where she settled.

Ellen’s parents were deported to Riga on the very last transport from Königsberg and shot on arrival. Her brother Heinz was forced to do slave labour and died a week after liberation, before Ellen could establish any contact.

Later in life Ellen became a close friend and supporter of the National Holocaust Centre and Museum and gave her testimony as long as she was able. Her testimony and the objects, documents and photographs she has donated continue to provide a crucial role in Holocaust education.