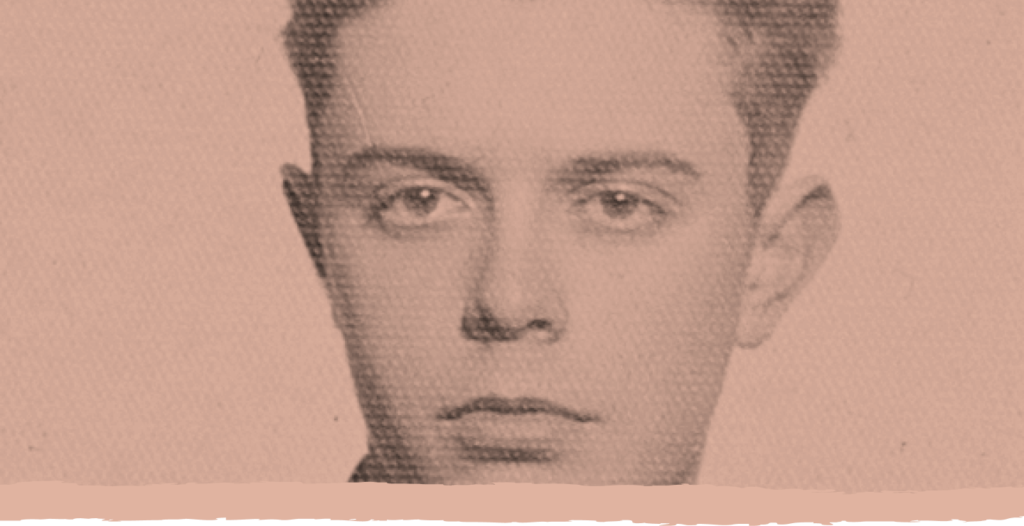

Julius Feldman was born on 24 December 1923, in Kraków, Poland. His family lived in the Podgórze district of the city.

When the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939, Julius and his family were immediately in danger.

Julius was acutely aware of the increasing anti-Jewish measures all around him. As the war, and persecution of Polish Jews, continued, he would feel the impact of both every day, sometimes walking home through deserted streets if there had been a deportation while he’d been at work.

Every day was high risk for the Feldman family, and their resistance was only effective for so long. One morning in 1943, when he was 19, Julius went to work after hiding his mother within the shop that they owned, and when he returned, she was gone. After searching for his father, Julius realised that he, too, had been taken. Julius ran to the next town to try and see the train he knew they would be on pass through, desperate to catch one last glimpse of his beloved parents. Sadly, by the time he arrived, the train had already gone.

1923

Julius went to work after hiding his mother within the shop they owned. When he returned, she was gone

Eventually, Julius, too, was captured and imprisoned at Płaszów concentration camp. He did not survive the Holocaust, and it is believed he was murdered in or around 1943, meaning he was just 19 years old.

1943

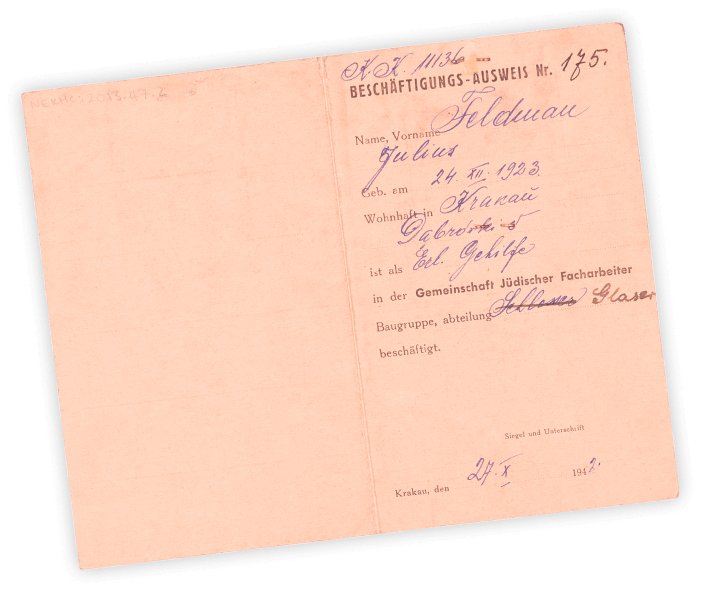

KK 11136

Work permit number: 175

Name: Julius Feldman

Date of birth: 24.12.22

Place of birth: Krakow

In the Jewish skilled worker community

Work unit: Glazier

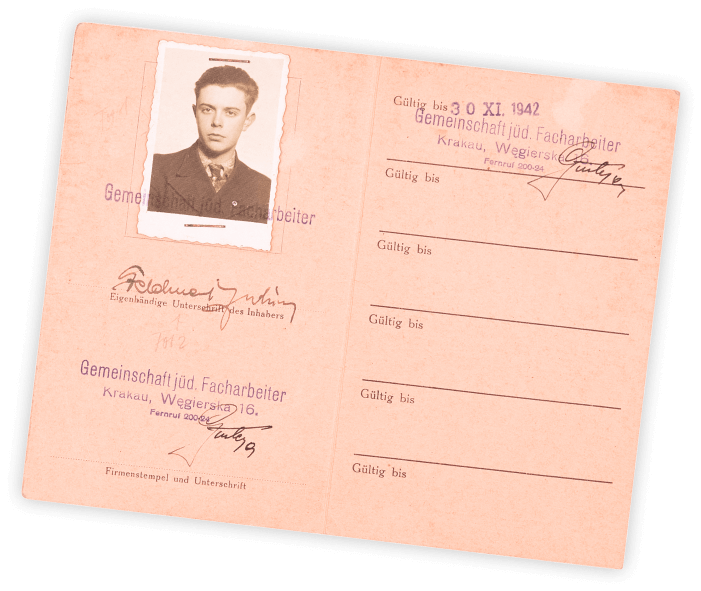

Inside left

Photograph of Julius Feldman

Julius’ signature

Official signature

Inside right

Date: 30.11.1942

Stamp reads: Skilled workers

Krakow address and telephone number

Official signature

This Ausweis card was issued to Julius in 1942 and had been applied for as his family were seeking permission to remain in Kraków.

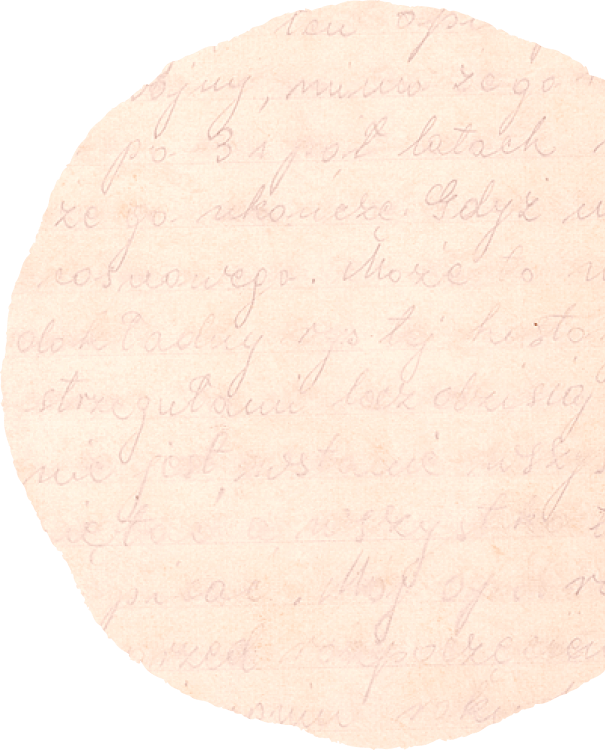

In his diary, which documents events from 1939 to 1943, Julius writes: “In order to stay in Kraków, you had to submit a petition requesting permission. Those who were accepted received an Ausweis (permit) but those who were rejected had to present themselves for deportation, with a 25-kilogramme parcel.

Things worked out well somehow and my father was among the first to receive an Ausweis. My mother, brother and I got ours some two weeks later.”

Diary and ID card are on display at The National Holocaust Centre and Museum