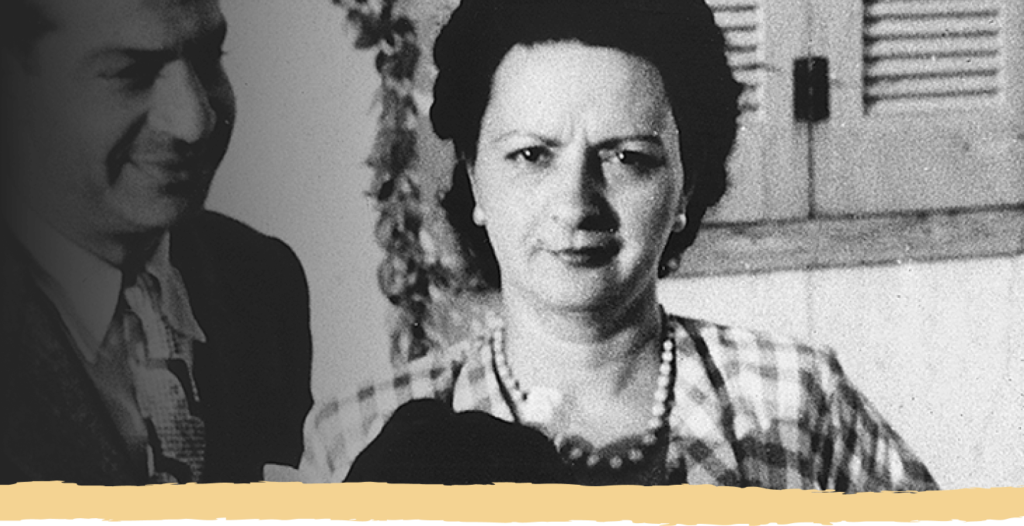

Eda de Botton-Siakki and her husband, Alvertos Siakkis, a lawyer, were a young Jewish couple living in Thessaloniki when the Germans occupied the city in 1941. Shortly afterwards, in April 1942, Eda gave birth to the couple’s first child, Reina.

With conditions imposed by the Nazis making life increasingly difficult for the city’s Jewish population, Eda and Alvertos had to act fast to ensure their – and their newborn daughter’s – safety.

Eda had Spanish citizenship, which gave her a chance of escaping, but only if she was no longer married to Alvertos, so the couple made the heartbreaking decision to divorce, and Eda reverted to her original surname, De Botton. Once divorced, Alvertos fled to the mountains where he joined the resistance movement. By that point, however, time had run out for Eda, and she was confined in the Thessaloniki ghetto despite her desperate efforts to flee.

1942

1946

To ensure her baby had the best chance of survival, the only option Eda had was to give her to a family friend, who in turn handed her over to a Catholic convent, where she could be looked after safely by nuns. In 1944, Eda was deported to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

Amazingly, Eda, Alvertos and Reina all survived. At the end of the war, in 1945, Eda was in a hospital, Alvertos was in Palestine, and Reina was still in the convent.

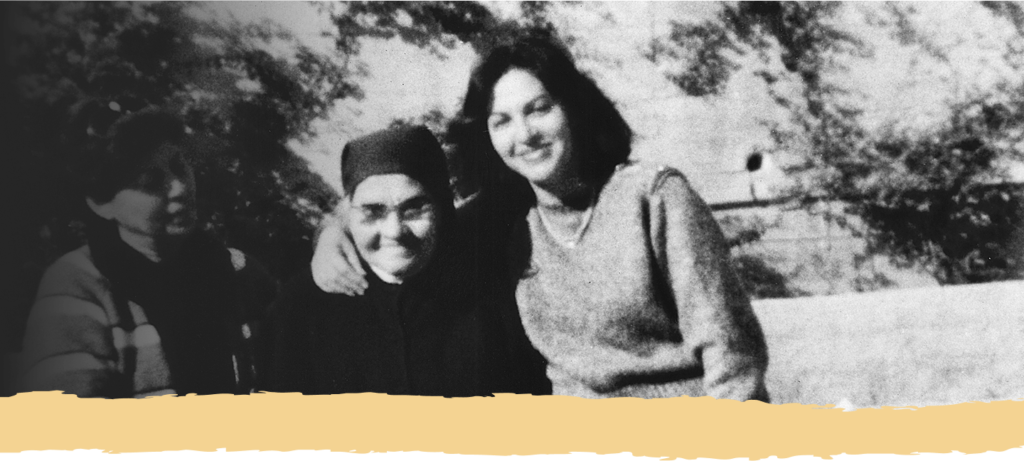

1984

While they had all survived physically, the emotional trauma of the Holocaust never left Eda, and she struggled to cope with the lasting effects of her experiences. She and Reina were reunited in Paris in 1946 after a prolonged search, but having been separated from her mother at a such an early age, Reina had no recollection of Eda and took a long time to accept her.

The rift the Holocaust created between them was never repaired.