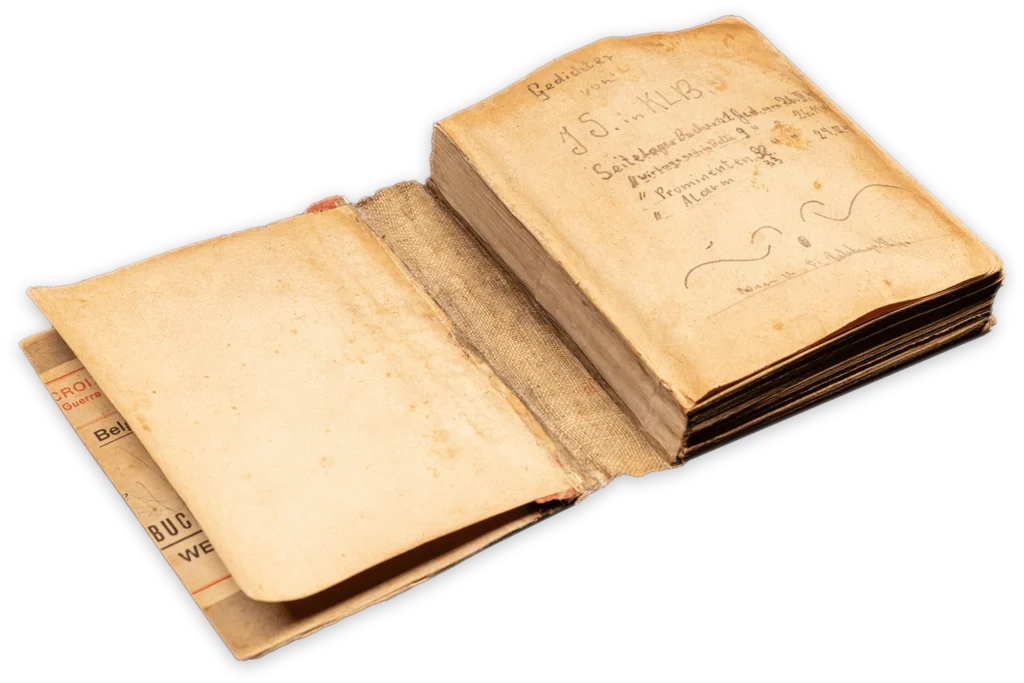

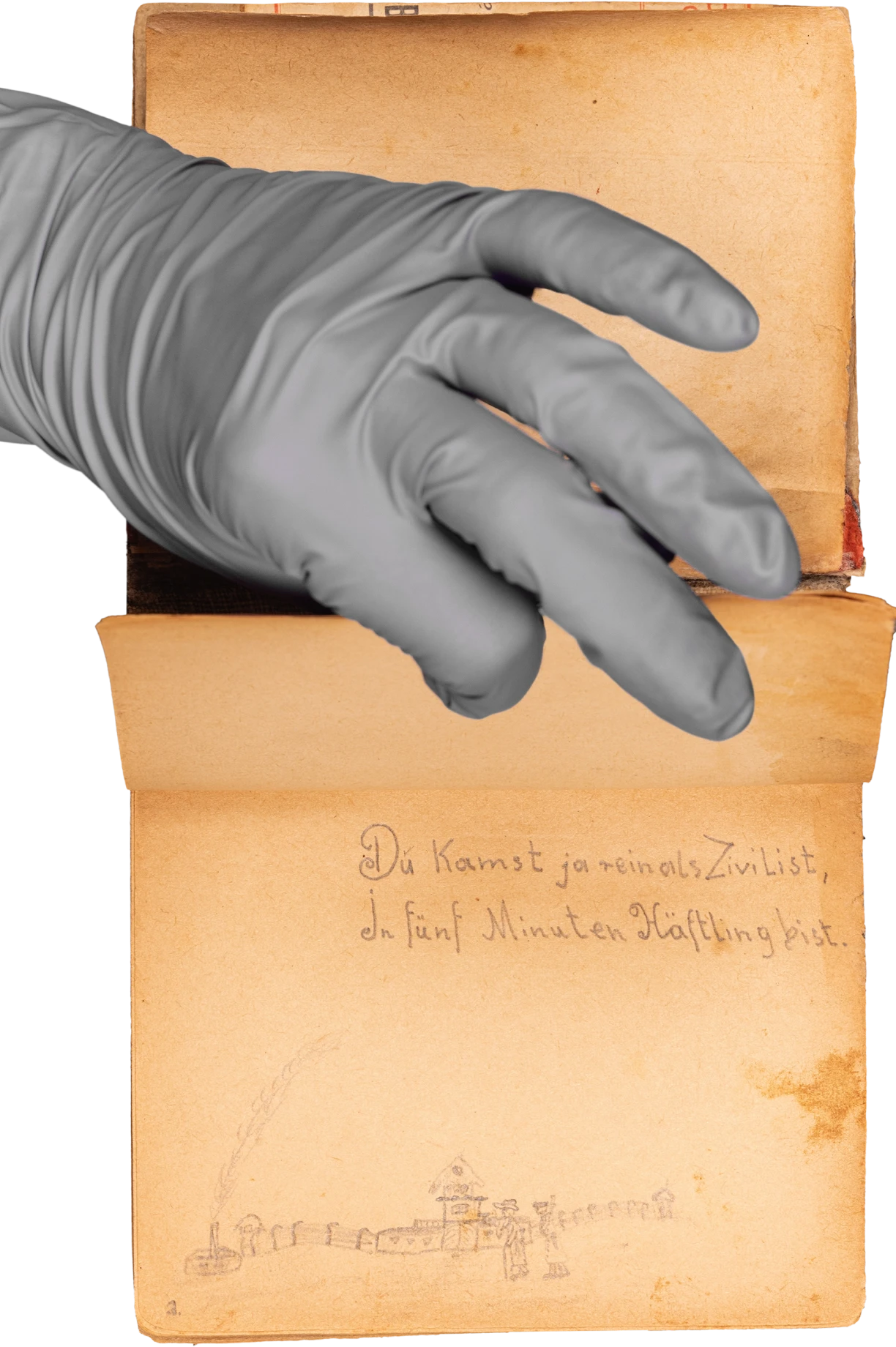

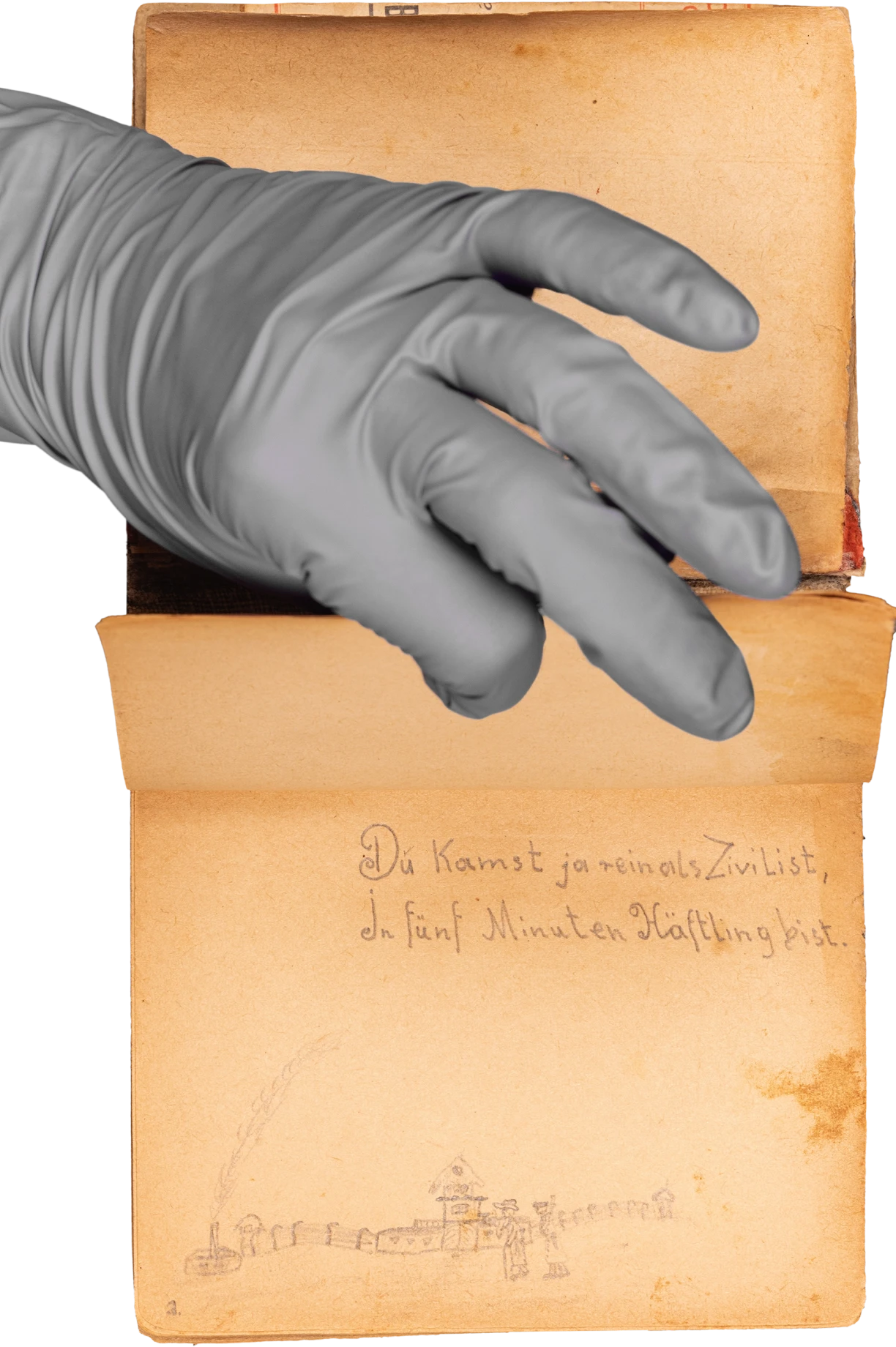

Mongo wrote this poetry book in Buchenwald Concentration Camp during 1944-1945.

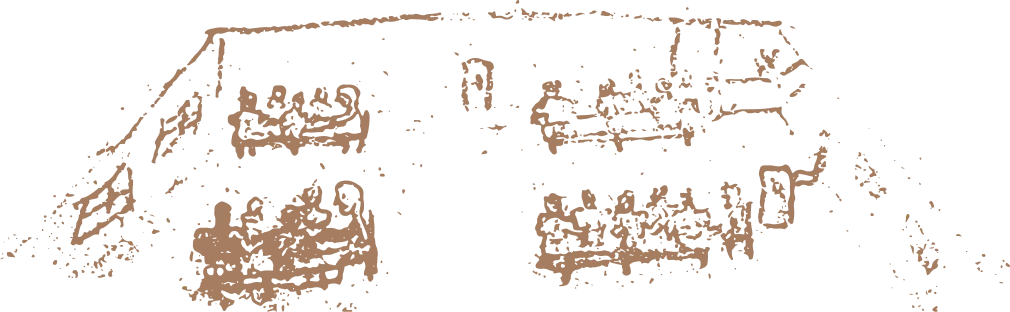

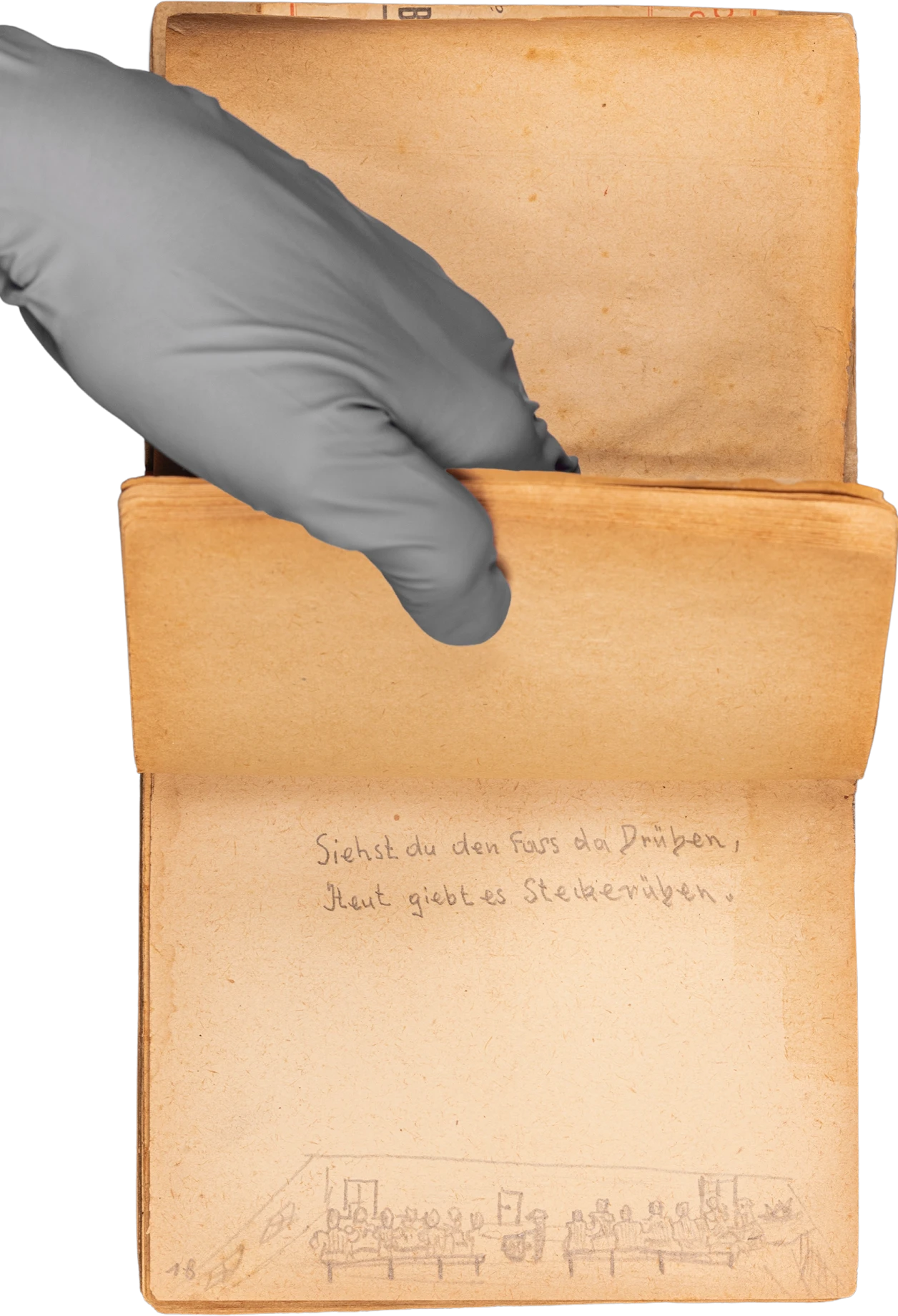

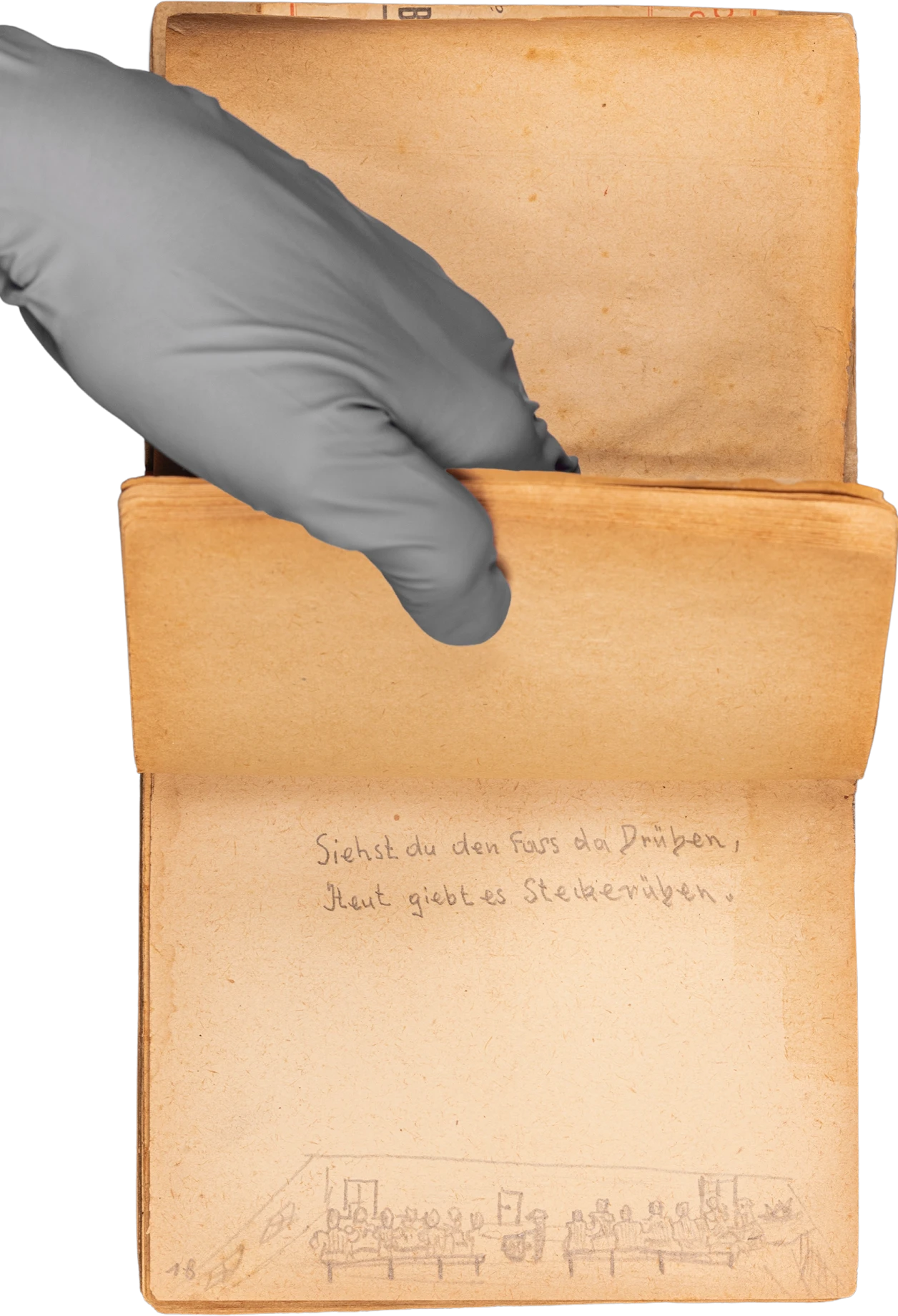

The book contains four poems, in which Mongo writes about everyday life in Buchenwald, including food, cold, work and roll calls. While many survivors have shared experiences similar to those Mongo references in his poems, the detailed illustrations, the perspective of a young person, and Mongo’s straightforwardness and lack of fear in the words make his book unique.

The writing and illustrations in the book are all in pencil. How Mongo managed to get hold of a notebook and pencil at Buchenwald remains a mystery.

The work was originally written in German, and the language is not always correct or standardised. Some words or phrases in the poems are difficult to interpret and translate in English because they have more than one meaning.

How Mongo managed to get hold of a notebook and pencil at Buchenwald remains a mystery

You come here as a citizen,

You’re just a prisoner to them

We were still in bed. In the dead

of night the whistle blew and all

at once our sleep was through

As we rush quickly through the door

To work, The Kapo shouts once more

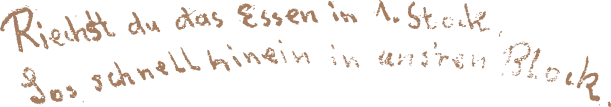

We smell the food from the first floor

As we rush quickly in once more

And over there see what’s to eat

Today the food we have is swede

What little food there is we’ve had

And yet my hunger’s still so bad

We were still in bed. In the dead

of night the whistle blew and all

at once our sleep was through

As we rush quickly through the door

To work, The Kapo shouts once more

We smell the food from the first floor

As we rush quickly in once more

And over there see what’s to eat

Today the food we have is swede

What little food there is we’ve had

And yet my hunger’s still so bad

While we don’t know the exact journey it took after Buchenwald, Mongo’s book of poems was discovered in the estate of Georges Hebbelinck, a political prisoner and former inmate of Buchenwald, after his death in 1964. It was donated by Hebbelinck’s heirs to the Archief en Museum van de Socialistische Arbeidersbeweging (AMSAB), which kindly donated it to Kazerne Dossin in 2013, which then loaned it to the Imperial War Museum in London, where it is currently on display in the Holocaust Galleries.

Today the book is very fragile, with pages disintegrating from the spine.

We are grateful to The Imperial War Museum and Kazerne Dossin for their support and for allowing us to share this artefact.